As you begin planning your layout, you should have already chosen a time period. This is critical since, your choice of locomotives and rolling stock depends on the time period that you choose to model. Another consideration will be, what type of railroad are you planning to model? Is it a mainline, a branch line or even a narrow gauge railroad? Depending on the time period and type of railroad, you may consider running a peddler freight, some passenger service, mainline service or even a combination of these. If you are modeling a prototype railroad, you may want to research the locomotives used by that railroad during the era you are planning to model. A good way to do that research is to join the historical society that focuses on the railroad you want to model. These historical societies sometimes offer models for sale and review models pertaining to the railroad that the historical society represents.

Once you purchase a locomotive or two, you will want to add some rolling stock. That means passenger or freight cars and once again you will want to consider what kinds of equipment were used during the period and type of railroad that you are modeling.

If you decide not to model a specific prototype railroad and free-lance instead, you have greater flexibility on choices of both motive power and rolling stock. The choice is yours.

Motive Power

There are a number of decidions to be made as you look at adding some motive power to your model railroad. Running steam vs. diesel locomotives is one of the larger decisions. Here again both era and prototype practices come to the forefront.

Steam or Diesel – Fantasy or Prototype the choice is yours

Steam or Diesel – Fantasy or Prototype the choice is yours

If you decide to model any time period prior to the end of WW II in 1945, steam will prevail. Although some early diesel locomotives were being used just prior to the 1940’s, widespread dieselization was put on hold for the duration of the war. In the decade just following the war, railroads speeded up the dieselization process. During this so called “Transition Period”, it was common to see both steam and diesel locomotives working side by side on many prototype railroads. It is safe to say that by the 1960’s, steam had all but disappeared except on logging and mining railroads. Even if you decide to model the post Steam Era, you still have to make sure that the diesel locomotives you decide to purchase actually existed during that time period. For instance, General Motors introduced the GP 38 in 1966, and some are still in use. So, if you model any time period between 1966 and today, you could realistically have a GP 38 on your model railroad. However, you would not want to run a GP 38 if you model the Transition Era.

Two New Haven diesels await the next call to duty. The larger is a 40-year-old Athearn “Blue Box” model that has been re-motored and equipped with a sound decoder.

Two New Haven diesels await the next call to duty. The larger is a 40-year-old Athearn “Blue Box” model that has been re-motored and equipped with a sound decoder.

Over the years, locomotives have been offered in kit form and “ready to run” (RTR). Special locomotives that would have limited appeal were (and are) offered in brass. However, since this Guide is designed for beginning model railroaders, the best bet is to stick with RTR locomotives. Even if you believe that you will operate your model railroad using good old fashioned DC power, it really does pay to purchase locomotives that are “DCC ready” to make it easier to upgrade at a later date. (More information about DC and DCC can be found in

Part 5 – Adding Power in this Guide.) Many types of locomotives – both steam and diesel – lettered for a wide variety of prototype railroads are available in all scales on the new and used market. If you freelance, sometimes undecorated locomotives are available and you can paint and then letter your own using decals or dry transfers. Alternatively, as many older models are disposed of my major railroads, the new owners will apply a patch over the old name with new marks. You could do the same with the road of your choice.

A modern coal train in HO scale.

A modern coal train in HO scale.

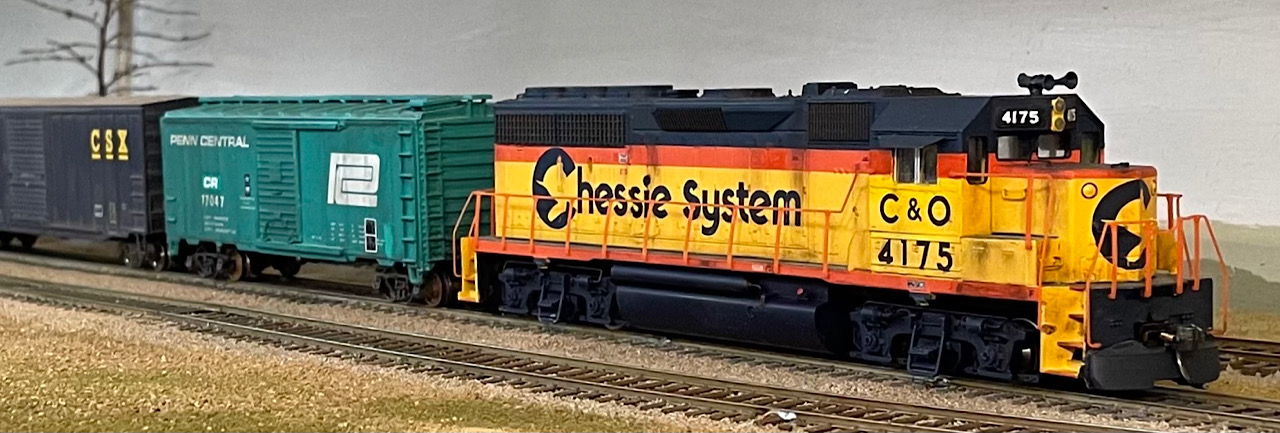

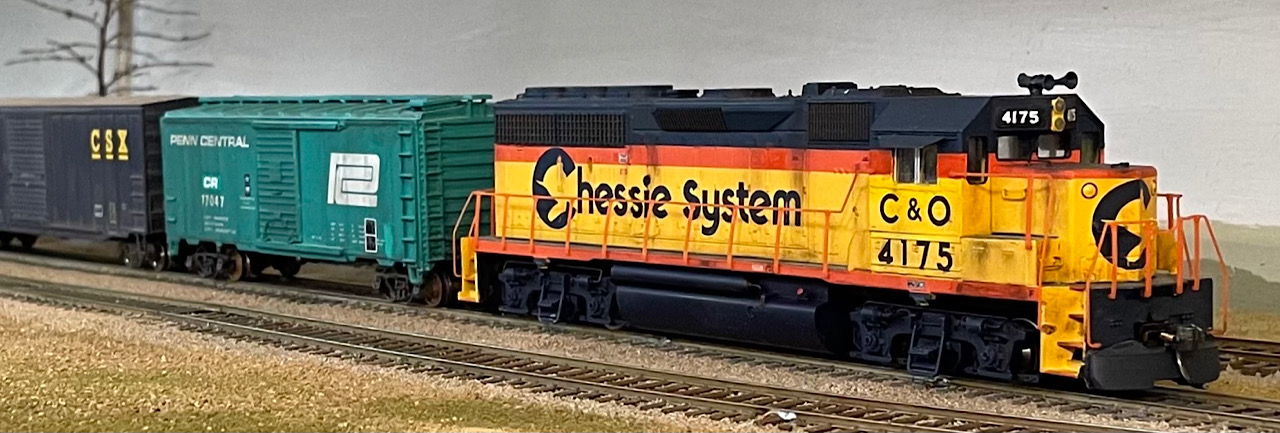

A freight train of the 1970's or later. The GP 40 was built between 1965 and 1971.

A freight train of the 1970's or later. The GP 40 was built between 1965 and 1971.

With maintenance, rebuilds, and modifications, locomotives can operate for many decades. Produced between 1966 and 1971, this GP38 is still working in Seattle on a BNSF local in August 2015.

Built between 1975 and 1992, the F40PH was a mainstay on Amtrak until replaced by newer power in the early 2000s. The F40PH can still be seen on commuter lines and Via Rail in Canada.

Good running and detailed locomotives and rolling stock are available in N scale, such as the Turbo train, which ran in the 1960s through 1980s, and the modern ES44AC, introduced in 2005.

Good running and detailed locomotives and rolling stock are available in N scale, such as the Turbo train, which ran in the 1960s through 1980s, and the modern ES44AC, introduced in 2005.

Specialized Motive Power

Besides locomotives, there are a number of other types of self-propelled rail vehicles that you can run on your model railroad. These include some cranes, log loaders, snow plows, “hand cars”, and a variety of self-propelled passenger cars. These were developed by the railroads to help cut the costs of running the ever-dwindling passenger service. Commonly called Doodlebugs or Railcars, they varied from critters banged together in the ‘back shop’ to the very sleek Budd Rail Diesel Car or RDC.

The RDC was produced by Budd from 1949 to 1962 and some are still running on tourist lines. The RDC and some of its predecessors are available RTR in several scales.

This Budd RDC belongs to the Conway Scenic Railroad in New Hampshire

This Budd RDC belongs to the Conway Scenic Railroad in New Hampshire

The Galloping Geese or the Rio Grande Southern RR are among the most famous of the ‘railcars’. These are available RTR in both HO and N scales. Here is a video of one in action at the Colorado Railroad Museum.

Before heading on to rolling stock, a few comments of the care and upkeep of motive power will be addressed.

Care and Upkeep

Recently manufactured model locomotives need very little maintenance. However, there are a few things to check that are easy for beginners – wheels in or out of gauge, dirty wheels and coupler height. These three things are easy to check and fix, and are the three items most likely to produce operating problems.

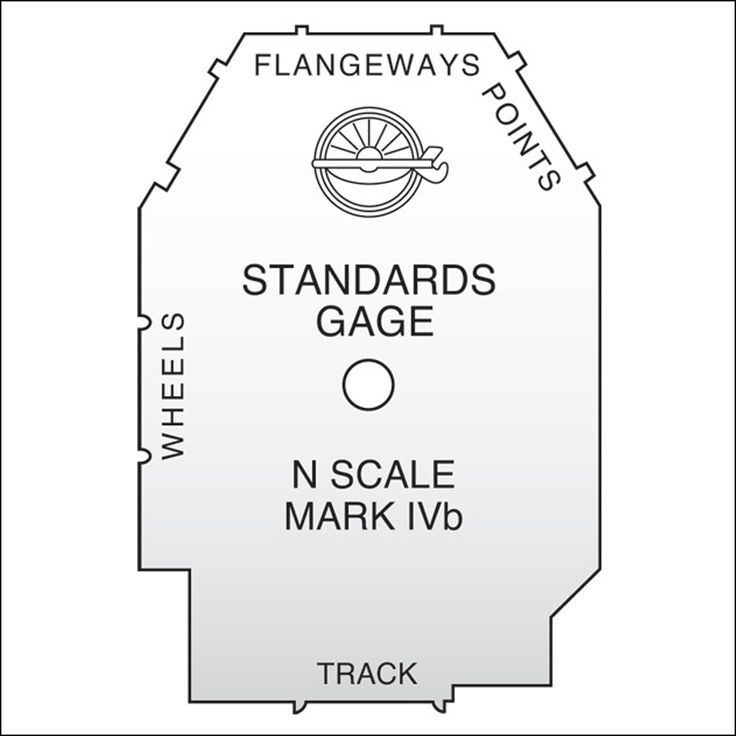

Checking wheel gauge is easy if you have an NMRA Standards Gage for your chosen scale. The one pictured here is the N-Scale Gage.

The lead trucks on steam locomotives are often the cause for derailments. To check if they are in gauge, turn the locomotive upside down and insert the wheels into the grooves that you see on the left side of the gage. You should be able to see daylight around the flanges of both wheels. If not, the spacing between the wheels on a diesel locomotive and on the lead truck of a steam locomotive can often be adjusted by holding the wheels on opposite sides of the axle - one in each hand - and gently twisting while either pushing or pulling the wheels. Steam locomotive drivers require more care to avoid binding the rods. You could also bring the locomotive to your local hobby shop for help. If the wheels on the lead truck are in gauge, but you are still having trouble with derailments, adding some weight over those front trucks can often solve the problem.

Smooth running locomotives require good electrical pickup through the rails of your track. Clean rails and clean wheels help promote this smooth running. Cleaning both with some isopropyl alcohol is a good place to start. The manufacturers Peco and Trix both offer very nice wheel cleaners. Both are easy to use and do a great job cleaning the wheels on locomotives.

The third and final tip on locomotive maintenance has to do with coupler inspection. If you are having trouble with rolling stock disconnecting from your locomotive, check that the coupler is closing properly and that it stays closed when applying a little opposing force between the locomotive and the piece of rolling stock. If it doesn’t, it is time to replace the offending coupler.

The other problem that can cause connection issues is the coupler height. Kadee makes a great coupler height gauge that all model railroaders should have mounted on a small piece of unpowered test track. Most coupler height adjustments can be made using the thin fiber washers offered by Kadee.

Eventually, motive power might need some lubrication. This usually requires removing the locomotive’s shell from the chassis. Follow the manufacturers’ directions for both removal of the shell and for the type and amount of lubrication.

GE 70 Ton Diesel showing perfect front coupler height using Kadee Gauge

GE 70 Ton Diesel showing perfect front coupler height using Kadee Gauge

Rolling Stock

Although many of us have seen prototype locomotives ‘running light’ (i.e., running without any cars attached), that is certainly not the norm. Operating a realistic model railroad requires pieces of “rolling stock”. Rolling stock comes in a wide variety of designs. Both era and locale will help dictate what rolling stock you add to your model empire. Types include boxcars, reefers (refrigerated cars), tank cars, flat cars, gondolas, open hoppers, closed hoppers, container carriers, car carriers, passenger cars, etc. Again, do some research and use the type of rolling stock that would be found in your era. Studies have been done on the relative quantities of each type of car that particular railroads would have in their roster. Generally, a railroad owned more boxcars than flat cars, for example. Still this varied depending on each railroad’s primary customers.

As you purchase more rolling stock, remember that if you are modeling an east coast railroad, there will be more ‘east of the Mississippi’ pieces of rolling stock on your model railroad than those from far western railroads.

Various types of rolling stock in Bruce DeYoung’s Jersey Highlands RR Yard – Notice all cars lightly weathered. (See Part 10 of this Guide for more information on weathering.

Various types of rolling stock in Bruce DeYoung’s Jersey Highlands RR Yard – Notice all cars lightly weathered. (See Part 10 of this Guide for more information on weathering.

An interesting article on one modeler’s approach to the mix of prototype road names and car types appeared in the November 2020 issue (Vol. 38, Number 8) of Red Markers, the newsletter of the Central New York Division of the Northeastern Region, NMRA. This link will bring you to the newsletter, and the article of interest is on page 5 of that issue.

http://cnynmra.org/index.php/newsletter/past-issues/rm-2020-vol38/132-rmvol38no08/file

Remember that “unit” trains are very common in the real world. You might need a good-sized fleet of open hoppers if your layout is based in ‘coal country’

Remember that “unit” trains are very common in the real world. You might need a good-sized fleet of open hoppers if your layout is based in ‘coal country’

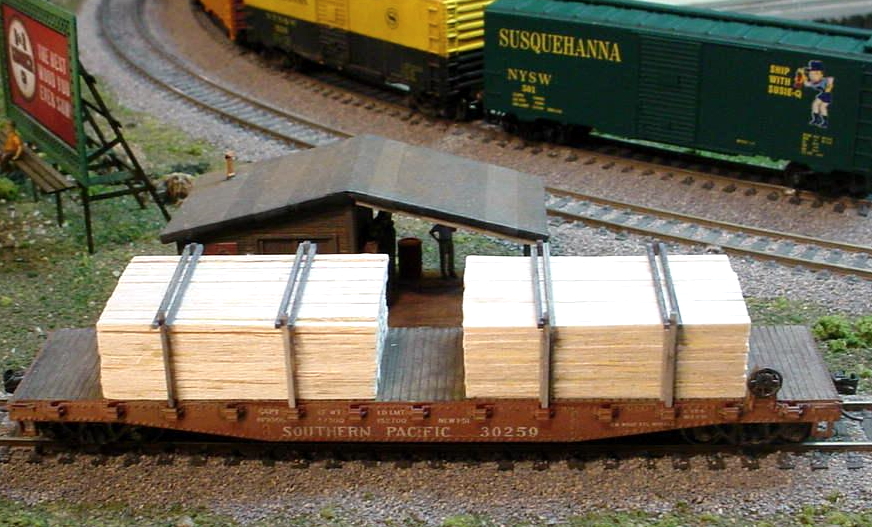

Open cars such as gondolas and flatcars look more interesting if you add loads to them. The following two pictures illustrate this.

If you plan on running some passenger car service, you need to take that into consideration when designing your track plan. Passenger cars are longer than almost all freight cars and require larger radius curves to operate smoothly and look ‘real’. However, passenger car service can add some interest to operations, so you might want to add a few cars. Many passenger cars have the couplers attached to the trucks (bogies) on the car, so don’t be surprised.

In many scales, rolling stock kits are still available. Some are quite easy to assemble and others have loads of tiny detail parts. As a beginner, you might want to start with some RTR rolling stock models and then add a few built from the easier kits.

Care and Upkeep

Rolling stock maintenance primarily focuses on the trucks (bogies), wheels, couplers, and the weight of the car.

The trucks need to swivel freely. If they hang up on anything under the car, that needs to be addressed. Coupler height and integrity concerns are the same as with motive power. Faulty couplers need to be replaced and coupler height adjusted. If the coupler height is way off, you might want to use spacers between the trucks and the underframe of the car if the couplers are low, or remove a bit off the bolster where the trucks attach if they are too high. Once again, a Kadee coupler height gauge is your friend.

Some wheelsets still come from the manufacturer with plastic wheels. Better long-term running can be achieved by replacing any plastic wheels with metal wheels. They run freer and do not accumulate dirt as quickly. Make sure that the wheels spin freely in the trucks.

The optimum weight of individual pieces of rolling stock varies with both the scale you are working in and the length of the car. Rolling stock models of the same type of car in a given scale can vary in weight from manufacturer to manufacturer, even if they are the same length. A scale 40’ boxcar weighs more than a scale 40’ flatcar. A train made up of light cars and heavy cars mixed together can cause derailments, especially on curves. There are many ‘late night discussions’ about the ideal weight for cars of a given length and scale, but there is general agreement that consistency of weight among a string of cars in a train improves performance.

As a starting point, the NMRA has a “Recommended Practice” for weighing cars. You can use a small postal scale to weigh your cars to see if they are near the recommended weight for the length of the car in your scale. Normally, cars are too light.

Stick-on weights are widely available to adjust the weight upward. These are normally added inside a closed car like a boxcar or reefer, and under a load in an open car like a flatcar or gondola.

Metal bar glued to the deck to add weight to this flat car. It will be hidden by the load

Metal bar glued to the deck to add weight to this flat car. It will be hidden by the load

The weight is now hidden by the load

The weight is now hidden by the load

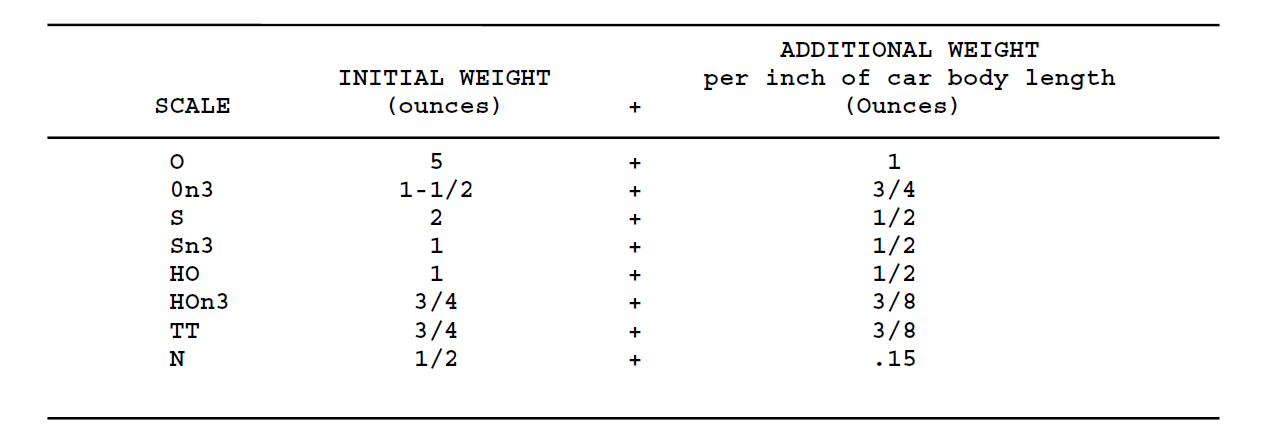

Here is the NMRA’s Recommended Practice RP-20.1 dealing with car weight.

To find the optimum weight of a given car, select your scale and find the "Initial Weight". Then take the "Additional Weight" and multiply this by the number of actual inches in the length of the particular car. Add this weight to the "Initial Weight" for the total Optimum Weight of the car. In HO, a 6-inch car should weigh 4 ounces. That is a 1 ounce minimum plus 1/2 ounce per inch of car. 1 + 3 = 4 ounces.

In conclusion, the purchase of a ready-to-run locomotive (steam or diesel) and a few pieces of RTR freight or passenger cars, and you will be on your way to operating your miniature railroad. This collection of motive power and rolling stock will undoubtedly grow with time and might begin to include rolling stock made from kits.

Videos and On-Line Resources